a bit of a bummer for us as we are planning to visit The Netherlands and other european countries this summer or maybe San Francisco but wait the show is coming to New York City this fall at the Frick Collection October 22, 2013 thru January 19,2014 says the NYTimes.

but never fear art travels well, so do we.

Girl with a Hoop Earring: Fun with Vermeer

Two beloved Vermeers have left Holland for a stint in the U.S. They’ll find their descendants stripped by Dalí, bedecked in toilet-paper rolls, and reincarnated by Cindy Sherman

The Girl with a Pearl Earring winked at me the other day.

San Francisco must be treating her well.

Vermeer’s enigmatic masterpiece has taken up residence at the de Young Museum, along with the 34 other Dutch Golden Age paintings on the road while their normal home, the Mauritshuis in the Hague, undergoes renovation.

The “Dutch Mona Lisa,” whose beauty and inscrutability have famously inspired art, fiction, product design, a Barbie, a Jonathan Richman song, and a whole lot of Flickr photos, doesn’t get out of Holland much, so for fans her U.S. tour—continuing at the High in Atlanta, and then the Frick—is like “the World Series, Super Bowl and Masters rolled into one magic moment,” as USA Today put it. At each venue, she will have a gallery all to herself.

Jan Vermeer, Girl with a Pearl Earring, ca. 1665, oil on canvas. To see her wink (sometimes), click here.COURTESY ROYAL PICTURE GALLERY MAURITSHUIS, THE HAGUE, BEQUEST ARNOLDUS DES TOMBE, 1903.

While The Girl With a Pearl Earring was hardly a wallflower at the Mauritshuis, she wasn’t quite the type to headline a show–until 2003, when she got her Hollywood break. Being played by Scarlett Johansson in Peter Webber’s film version of Tracy Chevalier’s novel brought the painting new fame; to the dismay of art historians, though, the audience sometimes concluded that the book’s main character, a maid who posed for Vermeer, was real.

Scholars don’t know who sat for the picture, which was not intended to be a specific portrait of anyone. That in itself wasn’t unusual in those days. What was unusual, says de Young curator Melissa Buron, was the three-quarter view, which highlights the sense that the woman is about to speak.

Adding to the Girl’s allure is her distinctive ultramarine turban—not exactly Dutch fashion at the time, either, but relatively easy to recreate in ours. Girl with a Bamboo Earring is from Awol Erizku’s photo series diversifying and updating art-history classics.

Awol Erizku, Girl with a Bamboo Earring, 2009, digital chromogenic print.COURTESY OF THE ARTIST AND HASTED KRAEUTLER GALLERY, NYC.

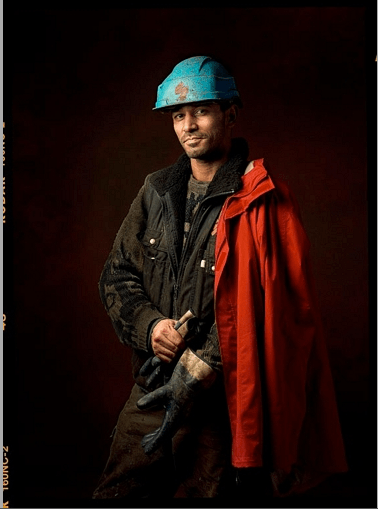

Dutch Old Masters get a different twist in Hendrik Kerstens’s color photographs, up through Saturday at James Danziger. Each one depicts the artist’s daughter Paula in get-ups that evoke 17th-century portraits, but with their lovingly rendered hoods and bonnets replaced by bubble wrap, tin foil, and other humble materials. These in turn inspired high fashion when Alexander McQueen used them as fodder for his fall 2009 collection.

Hendrik Kerstens, Paper Roll, 2008, pigment print.COURTESY DANZIGER GALLERY.

Meanwhile, further south, another iconic Vermeer is also in California for a spell: this Saturday the Getty opens a special installation of Woman in Blue Reading a Letter, on loan for six weeks while Amsterdam’s Rijksmuseum prepares for its reopening. She’ll be surrounded by other views of intimate interiors by Vermeer contemporaries including Jan Steen, Gerard ter Borch, and Pieter de Hooch.

This enigmatic beauty (who also has pearls, in a necklace on the table) has inspired speculation for centuries: Is the message from a lover? Does the map have a meaning? Is the woman pregnant, or just fashionably dressed?

Jan Vermeer, Woman in Blue Reading a Letter, about 1662-1663, oil on canvas.COURTESY RIJKSMUSEUM, AMSTERDAM. ON LOAN FROM CITY OF AMSTERDAM (A. VAN DER HOOP BEQUEST).

These open-ended stories were a lifetime provocation for Dalí, who admired Vermeer’s precision and reproduced the Dutch master’s content through the filter of his own unconscious. (Also, he set up an encounter between a rhino and a copy of The Lacemaker at the zoo, as you can see on YouTube).

In addition to recapitulating the The Lacemaker repeatedly, Dalí painted the mysterious Apparition of the Figure of Vermeer in the Face of Abraham Lincoln (what was he thinking about Lincoln?) and The Ghost of Vermeer of Delft Which Can Be Used as a Table (Phenomenologic Theory of Furniture-Nutrition), to name a few. Then there’s The Image Disappears (1938), an illusion that turns Vermeer’s Girl Reading a Letter at an Open Window into the profile of a bearded male—and back again. (Her head is his eye and her elbow his nose).

A study for the painting, now in “Drawing Surrealism” at the Morgan, tells us more about what was on Dalí’s mind. This one, clearly showing the optical illusion in the works, has two versions of the letter reader: one dressed, the other naked.

Salvador Dalí, Study for “The Image Disappears,” 1938, pencil on paper.©SALVADOR DALI, FUNDACIO GALA- SALVADOR DALI, ARTISTS RIGHTS SOCIETY (ARS), NEW YORK 2012 PHOTO ©2012 MUSEUM ASSOCIATES/LACMA, BY MICHAEL TROPEA PRIVATE COLLECTION.

It was Vermeer’s ability to confer nobility on the ordinary that attracted British photographer Tom Hunter. Hunter, who was living amidst squatters in Hackney, wanted to produce art that would help them in their struggle against authorities—not with “the usual stock of black and white images of the victims of society,” as he put it, but with serenity, beauty, dignity, light, and space. The girl in this photograph is reading an eviction order.

Tom Hunter, Woman Reading Possession Order, from the series “Persons Unknown,” 1997, cibachrome print.©TOM HUNTER, COURTESY THE ARTIST AND YANCEY RICHARDSON GALLERY.

Cindy Sherman captures Vermeer’s mood in black and white. Of course there is a letter-reader in the “Untitled Film Stills.”

Cindy Sherman, Untitled Film Still #5, 1977, gelatin silver print.COLLECTION MUSEUM OF MODERN ART, NEW YORK. HORACE W. GOLDSMITH FUND THROUGH ROBERT B. MENSCHEL. ©2013 CINDY SHERMAN.

If you can’t make it to the West Coast, remember that the East has plenty of Vermeers on public view, with five at the Met, three at the Frick, and three at the National Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C.–not bad considering that there are 36 extant works by the artist (including the one still missing from the Gardner theft).

Vermeer left relatively few documents about his sitters, or his symbols, but radiographs of one of the Met’s paintings yield tantalizing clues about his process. Originally, the figure in A Maid Asleep was accompanied by a man in the background and a dog in the doorway. Later, Vermeer replaced them with a mirror and a chair. With the love interest gone, we have to create the narrative ourselves.

Johannes Vermeer, A Maid Asleep, 1656–57, oil on canvas.THE METROPOLITAN MUSEUM OF ART, BEQUEST OF BENJAMIN ALTMAN, 1913 ACCESSION NUMBER: 14.40.611.

A squatter in Tom Hunter’s version of the scene.

Tom Hunter, A Woman Asleep, from the series “Persons Unknown,” 1997.©TOM HUNTER, COURTESY THE ARTIST AND YANCEY RICHARDSON GALLERY.

For The Music Lesson, Hiroshi Sugimoto photographed a wax tableau of the original painting installed in Madame Tussauds in Amsterdam.

Hiroshi Sugimoto, The Music Lesson, 1999, pigment print.©HIROSHI SUGIMOTO COURTESY PACE GALLERY.

The Pearl Earring girl pixelated in spools and made whole through the lens of an optical device, courtesy the art-history-riffing illusionist Devorah Sperber.

Devorah Sperber, After Vermeer 2, detail view, 2006, 5,024 spools of thread, stainless-steel ball chain and hanging apparatus, clear acrylic viewing sphere, metal stand.COURTESY OF THE ARTIST.

Museums are offering new ways to engage with Vermeer through social media. The Getty blog is asking people to send in a first sentence of the letter. The de Young Tumblr, following the Guardian’s lead, put out a call for imagined versions of the Girl’s story.

The next thing you know, Vermeer’s inscrutable beauties will be telling their own versions on Twitter. @girlwithapearlearring seems to be open.

Film still from Girl with a Pearl Earring.©JAPP BUITENDIJK.

Copyright 2013, ARTnews LLC, 48 West 38th St 9th FL NY NY 10018. All rights reserved.